A semi-sequel to this entry.

Over the last decade or so, the word “bromance” has entered the common vocabulary. A contraction of “brother” and “romance”, it refers to an intense but non-sexual friendship between two men.

Learning just recently that academics have named it “homosociality”, I’ve long thought nevertheless that the simple fact of male friendship and camaraderie is key to human evolution.

The male of Homo sapiens, is distinct from other primates for not being asocial. Female chimps, gorillas, bonobos and so on, are able to forge bonds with each other, even when they are not direct kin.

There is no friendship, however, between male primates, including those who are related by blood.

From what I have read about mammal ethology generally, solitary behaviour amongst males of this order of life, is the rule rather than the exception.

Somehow, the Homo line was able to extend the sympathetic drive inherent in the mammalian bond, to be a commanding instinct among the entire species.

The instinctual status of human sympathy is attested to, by how certain people manipulate it for their own benefit. Confidence artists, for example, often commence their scams by appearing to be infirm, or by regaling their mark with some “sob-story” or another.

Children, too, seek to avoid punishment for mischief by (as a friend put it years ago) “crying my way out of it.” Tears are a fascinating part of the human behavioural repertoire. Though expressions of sadness and distress are common amongst mammals at least, only anecdotal evidence exists of tears being shed by animals other than the human — even amongst close primate relatives such as chimpanzees and gorillas. During infancy and childhood, crying is as much or more so a response to actual physical harm or injury, as to hurt feelings.

But with maturity, crying is almost always an emotional as opposed to physical reaction. It is perhaps the most conspicuous example of how physiologically-integrated is the human primate into the social milieu. According to the abstract of a paper published by Dr. Oren Hasson of Tel Aviv university, “Multiple studies across cultures show that crying helps us bond with our families, loved ones and allies ... By blurring vision, tears reliably signal your vulnerability and that you love someone, a good evolutionary strategy to emotionally bind people closer to you.” According to Dr. Hasson, “"Crying is a highly evolved behavior. Tears give clues and reliable information about submission, needs and social attachments between one another. ... My analysis suggests that by blurring vision, tears lower defences and reliably function as signals of submission, a cry for help, and even in a mutual display of attachment and as a group display of cohesion."”

Most everyone can make themselves cry, but tears usually come involuntarily. This is why it has been viewed as shameful to cry, especially for men. Women frequently cry when in argument with their boyfriends or husbands, but female attestations of crying when alone demonstrate that they, too, are embarrassed about the “weakness” of tears.

Since it is either not possible (or extremely rare) for animals to cry, tears of sadness must be a product especially of Homo evolution. The sympathetic bond in hominids goes back a very long way, for to have evolved a special, involuntary faculty — tears — to arouse compassion automatically in others.

Selection pressures inherent in an environment of intense sociality, caused an adaptive change in biology for the Homo primate. Tear-ducts have been an essential part of the eyeball, as the sense organ evolved in multicellular lifeforms.

Excessive secretion of tears occurs throughout the animal kingdom, in response to contamination of the retina (people often excuse emotional tears by saying that “smoke or something is in my eye”). The ancestors of humans developed the ability to tear up in response to social, in addition to natural, stimuli (i.e., smoke).

Sobbing gives the physiognomy a striking resemblance to that of a sick person. Taking care of the ill and infirm is very ancient behaviour, too, as evidenced by Homo fossil specimens found without teeth or with crippling diseases or injuries that would have precluded them from taking care of themselves.

As noted, con-artists often pretend illness as a means of gain, but such a rouse is not always done for greed alone. People feign sickness simply for the sympathy it evokes, which is telling in itself. And, if typically involuntary, people can make themselves cry, as well, for manipulative purposes. Conversely, sadness can induce illness, either psychosomatically, or by suppressing immunity to virus and disease.

It is a vivid example of how culture affects the very physiology of the human primate. For the vast majority of the human race, sympathy is an instinct that is evoked by the appropriate stimuli, such as crying.

Most health-scam victims are shocked and ashamed at their own gullibility. They didn’t, as the saying goes, “hear alarm bells going off,” because their cold reason was overcome by the drive to help others in need. In spite of the neologism, “bromance” is thus very primal to the Homo family. Human uniqueness began not in any particular technical skill, but with the turn toward sociality by the hominid male.

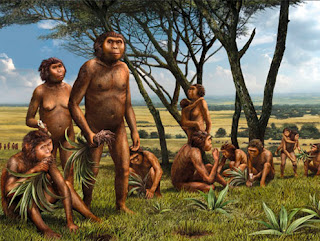

Evidence of male involvement in Homo social groups goes back a long way, at least to the “first family”, the set of adult and child fossils discovered by Donald Johanson in Africa, which date to at least three million years ago.

It isn’t only that the hominid male was able to bond with a family group, a remarkable turnabout from normal primate behaviour. It was even more so that Australopithecus (or later hominid) males learned how to get along with each other, which is very exceptional for a mammalian species.

Predator and forager, the asocial behaviour of the male is a result of selection pressures as well. The main evolutionary purpose of aggression for male mammals at least, is to establish territory for reproductive and sustenance needs. This will ensure that their genes, and not those of other males of their species, will be passed on.

For hominid males, though, reproductive success was assured by sociality, and not individualistic territoriality. Aggressiveness was retained as part of Homo behavioural repertoire. Except that this was practised socially as well.

In this, male aggression followed the normal mammalian pattern. Throughout the animal kingdom, mothers are driven to violence when their young are seen to be under threat. Bonding with the kinship group, Homo males used cooperative aggression to allay menace from others of their kind, and from different species as well (including other hominids).

Brutality carried out as vengeance for injury visited upon kin or comrade, is a commonplace in human history. Such aggression is provoked even (or especially) when the initiating harm is symbolic, as much as physical. Sympathy exists dialectically with aggression throughout the mammalian order (as with the “mama bear protecting her cubs”).

The involvement of males in the Homo social group, established a territorial ground expansive enough for complex social and cultural behaviour to take shape.

It came through the use of aggression as an expression of sympathy by the individual for the group. Long before humankind settled down in farms and cities, it had colonized all the continents but one.

This would have been impossible without the intense cooperation witnessed particularly in the hunting tribe, a cultural artefact responsible wholly or in part for the extinction of most land-dwelling mega-fauna (and many other creatures medium and small).

The skills and abilities honed by hunting, were institutionalized in the warrior band, the explicit purpose of which is to attack humans, not animals. Martial elites have dominated the rest of humankind throughout recorded history.

This was achieved pragmatically through the control of the means of destruction — weaponry. Just as important, though, was the “spiritual” part of the warrior ethos, which demands the surrender of mere egotistical concerns for the sake of the corps.

The career soldier in any era lives to practice selfless commitment to his “brothers”, right up to laying down his life for them. It is the pan-cultural tradition that goes under the name of “honour”, and which often inspires respect, even friendship, between those who previously fought on opposite sides.

Warriors lack respect for those who do not fight, hence the violence and brutality meted out to non-combatant populations during the conduct of war. The military has been the most prominent example of homosociality throughout history, but barracks’ life has apparently included plenty of active homosexuality as well.

This was famously the case with the armies of the Classical world, and more recently life in the Royal Navy was said to consist (in words often attributed to Winston Churchill) of “rum, sodomy and the lash.”

The warrior tolerance or encouragement of same-sex relations, may well have inspired the monotheistic faiths to forbid homosexuality outright. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all look to encourage sympathy in a principled and pacifist way anathema to the warriors’ bond, and toward all of humanity, regardless sex, race or status.

Practically, of course, each of the monotheistic faiths have had to fight holy war. But the conspicuous example of Christian homosociality was the monastery, in which participants were supposed abjure not only from aggression and other sin behaviours (such as having sex), but also to give up family life and other traditional means of belonging.

Interestingly, monasticism is not just discouraged, but forbidden outright in Islam, the same religion which uniquely and explicitly lays out the rules for just holy war, or jihad.

It was hominid-male sociality which, sooner or later, displaced the female as the centre of the kinship group among human primates. It has been periodically fashionable to suggest that during the time of the hunter-gathering economy, all human societies were matriarchal and thus peaceful and cooperative in character.

This was despoiled only with the rise of farming and civilization, and with these, warrior elites. It is true that virtually all civilizations have been highly patriarchal; of ancient cultures, only the Etruscans are believed to have granted any status at all to women. Perhaps tellingly, though, Etruscan dominance of the Italian peninsula was short-lived, falling with relative speed to the avowedly patriarchal Latins.

It isn’t entirely clear, however, that matriarchy prevailed prior to the rise of civilization. Certainly, this isn’t even the case with hunter-gatherer societies that survived into the historical era. Some are matrilineal, it is true, but others are strictly patriarchal. And regardless of family structure, in no hunter-gatherer society do the men behave peaceably. On the contrary, they are often more violent than those in agrarian or urbanized cultures.

Whatever happened during prehistory, though, there is good reason why patriarchy became the dominant mode of kinship as human beings became sedentary and civilized. It is that, paradoxically, males are more expendable than women. If hypothetically, a society were to lose most of its men, it could rebound in population quite easily, by having the survivors impregnate the rest of the women. But the converse is not true: not matter how many men a women has relations with, she will become pregnant by only one of them.

Thus it is that polygamy is extremely common throughout history — especially in war-like cultures — while polyandry (the marriage of more than one man to a single woman) is correspondingly rare.

As progenitors of the race, women were so valuable that they came to held as property by men, whose lives in turn were rated much cheaper when not in ownership of women. The ancient and common practice was for a conquering army to kill the men and enslave the women, who could give birth to the next generation of male slaves. Reducing women to the status of chattel, allowed warrior men to act upon their sympathetic drive mostly in regard to their fellow soldiers.

The intense homosociality necessary to create a domineering male elite, is compromised by the mundane and tender concerns inherent in family life. There must be an enduring tension, for men, inherent between family life and the brotherhood of arms (or of anything else).

Monotheistic religion attempted to direct the male away from a martial mentality, toward a marital one. The warrior ethos was promulgated almost as an ideal type in the Spartan polis, counterpart and rival to the Atticans during Classical times.

There, warriors were separated from their families physically as well as psychologically. With the onset of adolescence, boys were removed from the care of their mothers, sent to barracks for intense training and complete immersion into military life.

Upon adulthood, arranged marriages would occur, after which men and women lived apart (but for periodic assignations in which the husband would pretentiously or literally rape his wife). Whilst Spartan women remained in the domus to keep care of the young, the men kept rigidly to themselves, training for the next combat, conquering enemies, and otherwise engaging in homosexuality to an extent that scandalized even the Athenians.

The degree to which military success depends upon a homo-social esprit de corps, has been revealed in recent decades as women have been permitted to enter the armed services, even taking up positions in combat battalions.

Not long ago, for example, a retired Canadian supreme court justice issued a report, which found that sexual harassment was rife in the country’s co-ed military units. The American military, meanwhile, does not allow females to serve alongside men, or in combat at all, precisely because it would undermine unit cohesion, as apparently is the case with the Canadian and other armed forces that (unlike the U.S.) are remote from actual fighting.

Over the last decade or so, the word “bromance” has entered the common vocabulary. A contraction of “brother” and “romance”, it refers to an intense but non-sexual friendship between two men.

|

| Benacoop? copyright, 2013 Kevin Mazur |

Learning just recently that academics have named it “homosociality”, I’ve long thought nevertheless that the simple fact of male friendship and camaraderie is key to human evolution.

The male of Homo sapiens, is distinct from other primates for not being asocial. Female chimps, gorillas, bonobos and so on, are able to forge bonds with each other, even when they are not direct kin.

There is no friendship, however, between male primates, including those who are related by blood.

From what I have read about mammal ethology generally, solitary behaviour amongst males of this order of life, is the rule rather than the exception.

Somehow, the Homo line was able to extend the sympathetic drive inherent in the mammalian bond, to be a commanding instinct among the entire species.

The instinctual status of human sympathy is attested to, by how certain people manipulate it for their own benefit. Confidence artists, for example, often commence their scams by appearing to be infirm, or by regaling their mark with some “sob-story” or another.

Children, too, seek to avoid punishment for mischief by (as a friend put it years ago) “crying my way out of it.” Tears are a fascinating part of the human behavioural repertoire. Though expressions of sadness and distress are common amongst mammals at least, only anecdotal evidence exists of tears being shed by animals other than the human — even amongst close primate relatives such as chimpanzees and gorillas. During infancy and childhood, crying is as much or more so a response to actual physical harm or injury, as to hurt feelings.

|

| Didn't want him to cut it ALL off... www.whensallymetsally.co.uk |

But with maturity, crying is almost always an emotional as opposed to physical reaction. It is perhaps the most conspicuous example of how physiologically-integrated is the human primate into the social milieu. According to the abstract of a paper published by Dr. Oren Hasson of Tel Aviv university, “Multiple studies across cultures show that crying helps us bond with our families, loved ones and allies ... By blurring vision, tears reliably signal your vulnerability and that you love someone, a good evolutionary strategy to emotionally bind people closer to you.” According to Dr. Hasson, “"Crying is a highly evolved behavior. Tears give clues and reliable information about submission, needs and social attachments between one another. ... My analysis suggests that by blurring vision, tears lower defences and reliably function as signals of submission, a cry for help, and even in a mutual display of attachment and as a group display of cohesion."”

Most everyone can make themselves cry, but tears usually come involuntarily. This is why it has been viewed as shameful to cry, especially for men. Women frequently cry when in argument with their boyfriends or husbands, but female attestations of crying when alone demonstrate that they, too, are embarrassed about the “weakness” of tears.

Since it is either not possible (or extremely rare) for animals to cry, tears of sadness must be a product especially of Homo evolution. The sympathetic bond in hominids goes back a very long way, for to have evolved a special, involuntary faculty — tears — to arouse compassion automatically in others.

Selection pressures inherent in an environment of intense sociality, caused an adaptive change in biology for the Homo primate. Tear-ducts have been an essential part of the eyeball, as the sense organ evolved in multicellular lifeforms.

Excessive secretion of tears occurs throughout the animal kingdom, in response to contamination of the retina (people often excuse emotional tears by saying that “smoke or something is in my eye”). The ancestors of humans developed the ability to tear up in response to social, in addition to natural, stimuli (i.e., smoke).

Sobbing gives the physiognomy a striking resemblance to that of a sick person. Taking care of the ill and infirm is very ancient behaviour, too, as evidenced by Homo fossil specimens found without teeth or with crippling diseases or injuries that would have precluded them from taking care of themselves.

As noted, con-artists often pretend illness as a means of gain, but such a rouse is not always done for greed alone. People feign sickness simply for the sympathy it evokes, which is telling in itself. And, if typically involuntary, people can make themselves cry, as well, for manipulative purposes. Conversely, sadness can induce illness, either psychosomatically, or by suppressing immunity to virus and disease.

It is a vivid example of how culture affects the very physiology of the human primate. For the vast majority of the human race, sympathy is an instinct that is evoked by the appropriate stimuli, such as crying.

Most health-scam victims are shocked and ashamed at their own gullibility. They didn’t, as the saying goes, “hear alarm bells going off,” because their cold reason was overcome by the drive to help others in need. In spite of the neologism, “bromance” is thus very primal to the Homo family. Human uniqueness began not in any particular technical skill, but with the turn toward sociality by the hominid male.

|

| fathertheo.wordpress.com |

Evidence of male involvement in Homo social groups goes back a long way, at least to the “first family”, the set of adult and child fossils discovered by Donald Johanson in Africa, which date to at least three million years ago.

It isn’t only that the hominid male was able to bond with a family group, a remarkable turnabout from normal primate behaviour. It was even more so that Australopithecus (or later hominid) males learned how to get along with each other, which is very exceptional for a mammalian species.

Predator and forager, the asocial behaviour of the male is a result of selection pressures as well. The main evolutionary purpose of aggression for male mammals at least, is to establish territory for reproductive and sustenance needs. This will ensure that their genes, and not those of other males of their species, will be passed on.

For hominid males, though, reproductive success was assured by sociality, and not individualistic territoriality. Aggressiveness was retained as part of Homo behavioural repertoire. Except that this was practised socially as well.

In this, male aggression followed the normal mammalian pattern. Throughout the animal kingdom, mothers are driven to violence when their young are seen to be under threat. Bonding with the kinship group, Homo males used cooperative aggression to allay menace from others of their kind, and from different species as well (including other hominids).

Brutality carried out as vengeance for injury visited upon kin or comrade, is a commonplace in human history. Such aggression is provoked even (or especially) when the initiating harm is symbolic, as much as physical. Sympathy exists dialectically with aggression throughout the mammalian order (as with the “mama bear protecting her cubs”).

The involvement of males in the Homo social group, established a territorial ground expansive enough for complex social and cultural behaviour to take shape.

It came through the use of aggression as an expression of sympathy by the individual for the group. Long before humankind settled down in farms and cities, it had colonized all the continents but one.

This would have been impossible without the intense cooperation witnessed particularly in the hunting tribe, a cultural artefact responsible wholly or in part for the extinction of most land-dwelling mega-fauna (and many other creatures medium and small).

The skills and abilities honed by hunting, were institutionalized in the warrior band, the explicit purpose of which is to attack humans, not animals. Martial elites have dominated the rest of humankind throughout recorded history.

This was achieved pragmatically through the control of the means of destruction — weaponry. Just as important, though, was the “spiritual” part of the warrior ethos, which demands the surrender of mere egotistical concerns for the sake of the corps.

The career soldier in any era lives to practice selfless commitment to his “brothers”, right up to laying down his life for them. It is the pan-cultural tradition that goes under the name of “honour”, and which often inspires respect, even friendship, between those who previously fought on opposite sides.

Warriors lack respect for those who do not fight, hence the violence and brutality meted out to non-combatant populations during the conduct of war. The military has been the most prominent example of homosociality throughout history, but barracks’ life has apparently included plenty of active homosexuality as well.

This was famously the case with the armies of the Classical world, and more recently life in the Royal Navy was said to consist (in words often attributed to Winston Churchill) of “rum, sodomy and the lash.”

The warrior tolerance or encouragement of same-sex relations, may well have inspired the monotheistic faiths to forbid homosexuality outright. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all look to encourage sympathy in a principled and pacifist way anathema to the warriors’ bond, and toward all of humanity, regardless sex, race or status.

Practically, of course, each of the monotheistic faiths have had to fight holy war. But the conspicuous example of Christian homosociality was the monastery, in which participants were supposed abjure not only from aggression and other sin behaviours (such as having sex), but also to give up family life and other traditional means of belonging.

Interestingly, monasticism is not just discouraged, but forbidden outright in Islam, the same religion which uniquely and explicitly lays out the rules for just holy war, or jihad.

It was hominid-male sociality which, sooner or later, displaced the female as the centre of the kinship group among human primates. It has been periodically fashionable to suggest that during the time of the hunter-gathering economy, all human societies were matriarchal and thus peaceful and cooperative in character.

This was despoiled only with the rise of farming and civilization, and with these, warrior elites. It is true that virtually all civilizations have been highly patriarchal; of ancient cultures, only the Etruscans are believed to have granted any status at all to women. Perhaps tellingly, though, Etruscan dominance of the Italian peninsula was short-lived, falling with relative speed to the avowedly patriarchal Latins.

It isn’t entirely clear, however, that matriarchy prevailed prior to the rise of civilization. Certainly, this isn’t even the case with hunter-gatherer societies that survived into the historical era. Some are matrilineal, it is true, but others are strictly patriarchal. And regardless of family structure, in no hunter-gatherer society do the men behave peaceably. On the contrary, they are often more violent than those in agrarian or urbanized cultures.

Whatever happened during prehistory, though, there is good reason why patriarchy became the dominant mode of kinship as human beings became sedentary and civilized. It is that, paradoxically, males are more expendable than women. If hypothetically, a society were to lose most of its men, it could rebound in population quite easily, by having the survivors impregnate the rest of the women. But the converse is not true: not matter how many men a women has relations with, she will become pregnant by only one of them.

Thus it is that polygamy is extremely common throughout history — especially in war-like cultures — while polyandry (the marriage of more than one man to a single woman) is correspondingly rare.

As progenitors of the race, women were so valuable that they came to held as property by men, whose lives in turn were rated much cheaper when not in ownership of women. The ancient and common practice was for a conquering army to kill the men and enslave the women, who could give birth to the next generation of male slaves. Reducing women to the status of chattel, allowed warrior men to act upon their sympathetic drive mostly in regard to their fellow soldiers.

The intense homosociality necessary to create a domineering male elite, is compromised by the mundane and tender concerns inherent in family life. There must be an enduring tension, for men, inherent between family life and the brotherhood of arms (or of anything else).

Monotheistic religion attempted to direct the male away from a martial mentality, toward a marital one. The warrior ethos was promulgated almost as an ideal type in the Spartan polis, counterpart and rival to the Atticans during Classical times.

|

| supermanherbs.com |

There, warriors were separated from their families physically as well as psychologically. With the onset of adolescence, boys were removed from the care of their mothers, sent to barracks for intense training and complete immersion into military life.

Upon adulthood, arranged marriages would occur, after which men and women lived apart (but for periodic assignations in which the husband would pretentiously or literally rape his wife). Whilst Spartan women remained in the domus to keep care of the young, the men kept rigidly to themselves, training for the next combat, conquering enemies, and otherwise engaging in homosexuality to an extent that scandalized even the Athenians.

The degree to which military success depends upon a homo-social esprit de corps, has been revealed in recent decades as women have been permitted to enter the armed services, even taking up positions in combat battalions.

Not long ago, for example, a retired Canadian supreme court justice issued a report, which found that sexual harassment was rife in the country’s co-ed military units. The American military, meanwhile, does not allow females to serve alongside men, or in combat at all, precisely because it would undermine unit cohesion, as apparently is the case with the Canadian and other armed forces that (unlike the U.S.) are remote from actual fighting.